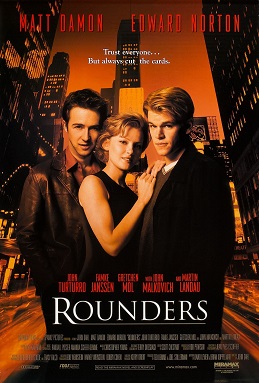

Twenty years ago, the film Rounders brought the poker variation known as “no-limit Texas hold'em” to

the wider public consciousness. The movie inspired thousands of

home-game players to pursue the game, including a young Tennessee

accountant named Chris Moneymaker, who achieved his own “Hollywood

ending” by winning the 2003 World Series of Poker Main Event and

launching the decade's “poker boom”.

If you've ever watched the TV coverage

of no-limit hold'em poker tournaments, you've seen how dramatic some

of the confrontations between players can be. If you watch closely,

you can see how the action of these high-stakes tournaments can add

intrigue and tension to your story.

Character Is As Character Does, Not As Character Says

One of the most dramatic aspects of TV

poker tournaments is the tension that the players show as they must

make a crucial decision. In most cases, the player will remain silent

for minutes at a time while they deliberate whether to fold their

hand, call the bet, or raise the stakes.

While such a long silent period in a

screenplay may not always work, screenwriters should understand how

to create tension from the situation, rather than from extensive

dialogue. Since poker players are not allowed to tell the truth when

asked about their cards during a hand, screenwriters should apply

that rule and put their characters in positions that require them to

lie and increase the tension in their scenes.

Keep The Audience In The Know

Another appealing aspect of TV poker

tournaments is the “hole card cam”, which allows the TV viewers

to see the cards each player holds. (NOTE: The "hole card cam" was invented by Henry Orenstein, a Polish immigrant and Holocaust survivor who also helped launch the "Transformers" toy line in the U.S.) While the audience is privy to

this information, the other players aren't. This information allows

the audience to recognize when a player is bluffing, or when they

have the best hand, which keeps the viewer invested in watching the

results.

While many rookie writers value the

“twist” ending, this technique can come across as more of a way

for the writer to show off, rather than a way to keep the audience

engaged. The classic horror trope of showing the killer on one side

of the door and the soon-to-be victim on the other has kept audiences

engaged for decades. Not only is it not a sin to reveal information

to the audience before the characters know, it can keep the audience

riveted to see the character's reaction when they find out.

Around The Turn And Down The River

After each player receives their two

hole cards and decides whether they want to stay in the hand, the

dealer puts out three cards on the table, face-up, for each remaining

player to use. These three cards are collectively known as “the

flop”. After another round of betting, the dealer puts out a fourth

card, called “the turn”. Another round of betting ensues, and the

dealer puts out the fifth community card, called “the river”. The

remaining players show their hands in a “showdown” at the end of

the hand.

This structure bears a resemblance to

the “three-act structure” often taught in most screenwriting

classes. The character starts off with the hand they're dealt, and

must make a decision to proceed with their journey. The character

“flops” into a new situation at the start of Act II and

encounters new allies (a strong hand) or new enemies (a weak hand).

The story takes a “turn” at the midpoint of Act II, then the

character takes a trip down a menacing “river” at the start of

Act III, leading up to a “showdown” with the antagonist.

Standing Still Is Not An Option

In no-limit hold'em, two players are

required to make minimum “blind” bets before the hand starts to

ensure that at least some chips are already in the pot. In tournament

play, the minimum bets increase at specific time increments. As the

blinds go up, the player's holdings get relatively smaller, even if

they maintain the same amount of chips. The increasing minimum bets force players with "short stacks" into desperate moves to stay alive.

In all types of fiction, but especially

in screenwriting, stasis equals death, at least the death of the

audience's interest. When the character chooses to stand still, the

world will still move on around them—and, quite possibly, run over

them. The writer must keep the character moving, either physically or

emotionally or both, to keep the story going and to maintain the

audience's interest.

Heads-Up To The Finish

When the final two players of the

tournament remain, they face off in “heads-up” play. These final

hands are often as much about will and skill as they are about cards

and chips. The final two players may have clashed previously over the

course of hours or days, but now it's for all the marbles.

Whether it's poker, boxing, MMA, or

tennis, audiences love to see a great one-on-one matchup. The same

appeal holds in screenplays. Whenever the writer can set up a

climactic confrontation between the protagonist and the antagonist,

whether that confrontation uses fists, guns, legal tactics, or

emotional manipulation, the audience will want to see who wins.

All In

The most thrilling part of any no-limit

poker hand is when one player bets all their chips on a single hand.

If they win, they double up and stay in the tournament. If they lose,

it's “Wait Til Next Year.” This moment comes when the player says

two simple words: “All In”.

As a writer, you have to risk a lot to

put your story on paper. You have to risk putting in long hours for

little or no reward. You have to risk missing out on fun times with

friends and family to work on your story. You have to risk feeling

like your story isn't good enough for anyone to want to read or see.

Just like in poker, the only way to win

at the screenwriting game is to go “All In”.

If you want your story to be a winner,

Story Into Screenplay offers a wide range of script services,

including coverage reports, rewrite services, and both live and

online hourly consultations.

You can email Story Into Screenplay at

storyintoscreenplayblog(at)gmail(dot)com, or send a message through

the Facebook page.

No comments:

Post a Comment